Introduction

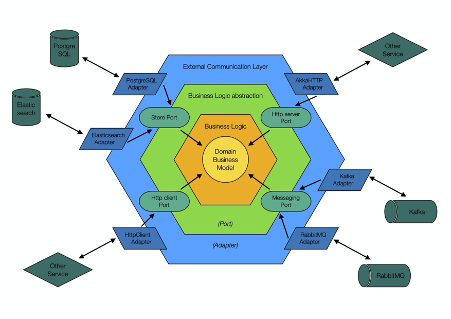

The hexagonal architecture (also called “ports and adapters”) is an architectural pattern used in software design designed in 2005 by Alistair Cockburn.

The hexagonal architecture is allegedly at the origin of the microservices architecture.

What it Brings to the Table

The most used service architecture is layered. Often, this type of architecture leads to dependencies of business logic from external contract (e.g., database, external service, and so on). This brings stiffness and coupling to the system, forcing us to recompile classes that contain the business logic whenever an API changes.

Loose coupling

In the hexagonal architecture, components communicate with each other using a number of exposed ports, which are simple interfaces. This is an application of the Dependency Inversion Principle (the “D” in SOLID).

Exchangeable components

An adapter is a software component that allows a technology to interact with a port of the hexagon. Adapters make it easy to exchange a certain layer of the application without impacting business logic. This is a core concept of evolutionary architectures.

Maximum isolation

Components can be tested in isolation from the outside environment or you can use dependency injection and other techniques (e.g., mocks, stubs) to enable easier testing.

Contract testing supersedes integration testing for a faster and easier development flow.

The domain at the center

Domain objects can contain both state and behavior. The closer the behavior is to the state, the easier the code will be to understand, reason about, and maintain.

Since domain objects have no dependencies on other layers of the application, changes in other layers don’t affect them. This is a prime example of the Single Responsibility Principle (the “S” in “SOLID”).

How to Implement it

Let’s now have a look on what it means to build a project following the hexagonal architecture to better understand the difference and its benefit in comparison with a more common plain layered architecture.

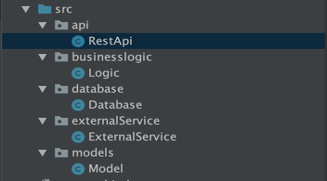

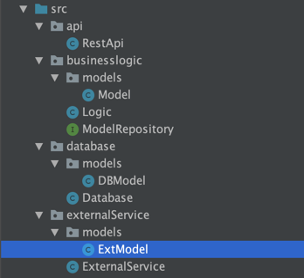

Project layout

In a layered architecture project, the package structure usually looks like the following:

Here we can find a package for each application layer:

- the one responsible for exposing the service for external communication (e.g., REST APIs);

- the one where the core business logic is defined;

- the one with all the database integration code;

- the one responsible for communicating with other external services;

- and more…

Layers Coupling

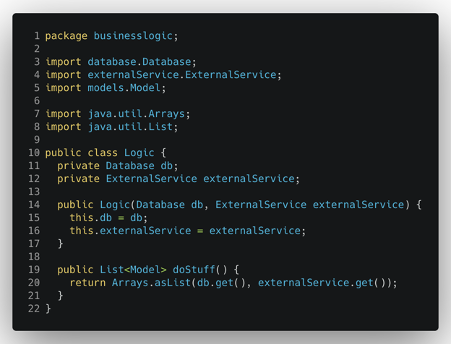

At first glance, this could look like a nice and clean solution to keep the different pieces of the application separated and well organized, but, if we dive a bit deeper into the code, we can find some code smells that should alert us.

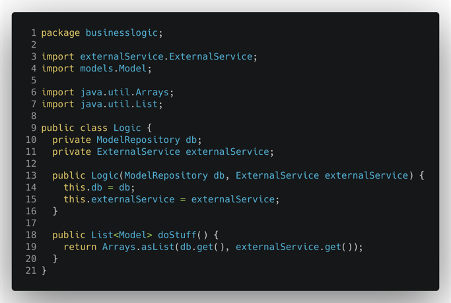

In fact, after a quick inspection of the core business logic of the application, we immediately find something definitely in contrast with our idea of clean and well defined separation of the various components. The business logic that we’d like to keep isolated from all the external layers clearly references some dependencies from the database and the external service package.

These dependencies imply that in case of changes in the database code or in the external service communication, we’ll need to recompile the main logic and probably change and adapt it, in order to make it compatible with the new database and external service versions. This means that we need to spend time on this new integration, test it properly and, during this process, we expose ourselves to the introduction of some bugs.

Interfaces to the Rescue

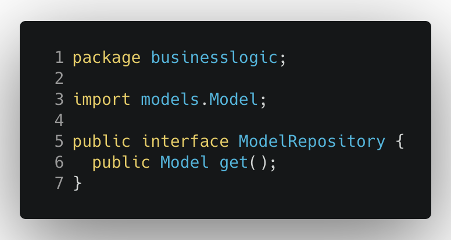

This is where the hexagonal architecture really shines and helps us avoid all of this. First we need to decouple the business logic from its database dependencies: this can be easily achieved with the introduction of a simple interface (also called “port”) that will define the behavior that a certain database class needs to implement to be compatible with our main logic.

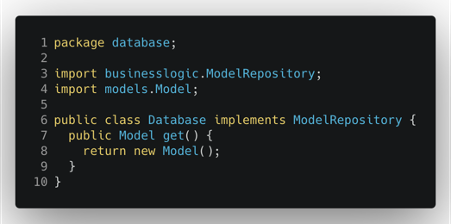

Then we can use this contract in the actual database implementation to be sure that it’s compliant with the defined behavior.

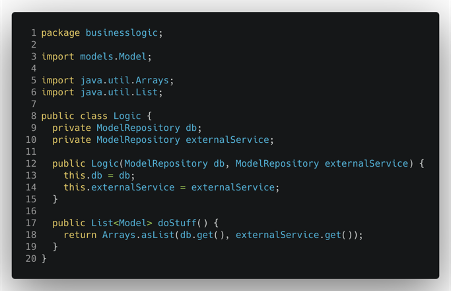

Now we can come back to our main logic class and, thanks to the changes described above, we can finally get rid of the database dependency and have the business logic completely decoupled from the persistence details.

It’s important to note that the new interface we introduced is defined inside the business logic package and, therefore, it’s part of it and not of the database layer. This trick allows us to apply the Dependency Inversion Principle and keep our application core pure and isolated from all the external details.

We can then apply the same approach to the external service dependency and finally clear the whole logic class of all its dependencies from the other layer of the application.

DTO for model abstraction

This already give us a nice level of separation, but there is still room for improvement. In fact if you look at the definition of the Database class you will notice that we are using the same model from our main logic to operate on the persistence layer. While this is not a problem for the isolation of our core logic, it could be a good idea to create a separate model for the persistence layer, so that if we need to make some changes in the structure of the table, for example, we are not forced to propagate the changes also to the business logic layer. This can be achieved with the introduction of a DTO (Data transfer object).

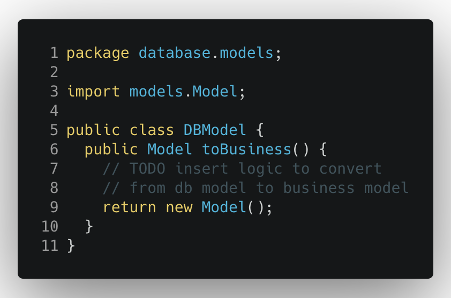

A DTO is nothing more that a new external model with pair of mapping function that allow us to transform our internal business model to the external one and the other way around. First of all, we need to define the new private model for our database and external service layers.

Then we need to create a proper function to transform this new database model into the internal business logic model (and vice versa based on the application needs).

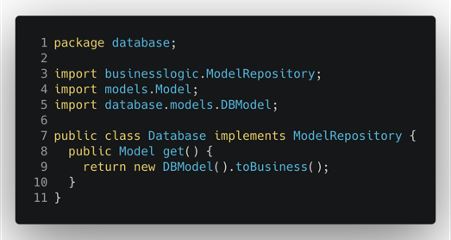

Now we can finally change the Database class to work with the newly introduced model and transform it into the logic one when it communicates with the business logic layer.

This approach works very well to protect our logic from external interference, but it has some consequence. The main one is an explosion of the number of the models, when most of the time the models are the same; the other one is that the logic about transforming models can be tedious and always need to be properly tested to avoid errors. One compromise that we can take is starting only with the business models (defining them in the correct package) and introduce the external models only when the two models diverge.

When to embrace it

Hexagonal architecture is no silver bullet. If you’re building an application with rich business rules that can be expressed in a rich domain model that combines state with behavior, then this architecture really shines because it puts the domain model in the center.

Combine it with microservices architecture and you’ll get a future-proof evolutionary architecture.