The JAMStack Proposition

With the surge in popularity of JavaScript frameworks, Node and container technologies, the past years have seen the rise of microservices as the leading pattern in the architecture of distributed applications on the Web; the lingua franca of these applications being, of course, APIs. Developers adopting these modern tools for frontend environments have though faced emerging challenges when dealing with search engine optimization, rendering the content and serving the applications compared to the common LAMP stack, where PHP does the bulk of the work and JavaScript only provides the interactions and dynamic elements.

From Client Side to Hybrid

While in the past using frameworks on the client side meant single page applications, using “hacks” such as the hashbang to provide navigation, in recent years the leading JavaScript frameworks embraced the hybrid approach in rendering, where both the server and the client would run the same virtual DOM and reconnect on the browser later, “rehydrating” the application on the client. This way, applications supported both the common navigation controls of the browser and provided accessibility to users with older browsers or even no JavaScript, since the page is readily available on the server. This provided improved performance on the first load, and supported the traditional spiders from search engines.

However, this meant:

- having an improved developer experience as the entire application uses only JavaScript and HTML, with a single code base…

- …but Node doesn’t actually support the same modules and featuresets of a browser

- taking a hit on a number of metrics, such as Time To First Byte and Time To Interactive, as the code runs on both ends

- relying on an increasingly complex deployment on the server compared to traditional shared hosting

- using “brute force” solutions to prerendering and caching applications, such as headless browsers

Limits of CMSs

Many modern web applications are still nothing more than glorified lists of contents, sometimes enabling modest interactions – such as filtering or sorting contents -, providing taxonomies and interacting with limited components – such as forms for comments or the search bar. As most of the content is static, a complete frontend solution is eventually considered an added cost compared to existing, monolith CMSs; they still offer big communities, a plethora of themes and plugins, and well rodated interfaces for content creators.

Yet, these CMSs still do not provide the same speed or developer experience as the applications written for Node, which can be started on any machine with nothing more than the Node runtime and have very fast cycles for changes. Moreover, they usually have limited support for components, or restrict them to the content side, while requiring the developer to code in additional custom parts for the rest of the page, often in a different language than the one spoken by the browser. Interaction is still tackled on, with JavaScript being unable to cross the boundaries of the single static page.

Last but not least, popular CMS such as WordPress come with larger surface areas for attack as they’re both incredibly popular and the very same endpoint for both the backend and the frontend; hosted on the same old machine, with the same address for both: subject to varying degrees of loads which might need horizontal scaling, creating issues for the cache.

Enter the Static Sites Generators

Even if CMSs can definitely render pages quickly and avoid the lengthy reconciliation with the browser’s context, they still require a server and dedicated support, with a plurality of codebases and a bad experience for the developer that does not have everything on hand on the local machine, or might not even have the required knowledge to deal with all issues in this tightly coupled project.

Static websites, instead, have no server loading times; require no session on the server, no instance of Linux running, and no real requirements other than a web server to deliver the resources. They can even live off incredibly cheap storage, such as S3 from Amazon.

A Modern Solution to Static Content

While traditional frameworks such as Jekyll or Hugo are fast and still a good solution, the new frameworks that have entered the space in the last years (such as Gatsby, Gridsome, Nuxt and Next.js) have took static sites to the future. Learning the lessons from hybrid applications and SPAs, they rely on improved tooling running on Node; modern web frameworks are now first class – improving both UX and developer experience.

They feature:

- complete SEO support – as pages are just HTML and CSS as before

- no need for a running service; deploy simply delivers the static files to the CDN

- improved performance on all metrics, and well engineered solutions for smaller JavaScript bundles and pipelines for other resources

- the same complex interactions of a SPAs, such as transitions and persistent state, and the same tools (like Webpack, Parcel, etc.)

- support for content from many sources: static files, version repositories, headless CMSs, APIs and more

Frameworks such as Gatsby and Gridsome take a page off the CMS’s playbook by offering solutions to different needs in the form of themes and plugins, yet retaining a single cohesive codebase with dependencies handled through the very same ecosystem of JavaScript, well familiar with developers already used to working with modern frameworks. They also come with configurations for older browsers, solving the rebus of packagers, and simple commands to either build or start a development service.

The reduction in complexity is significant. A streamlined frontend solution enables developers to focus on the core experience of users instead of wasting time on configuration. The absence of an actual service running the pages allows the website to run just about everywhere, letting backend developers focus on the business logic, and in between, APIs representing the contract between the two sides. DevOps have one less thing to be concerned about. It is the JAMstack: JavaScript, APIs, and markup languages.

Challenges of the JAM Stack

The massive improvements brought forth by the stack still face issues that many of the other solutions don’t, and by the nature of static contents; consequently, its strong points also represent its main pain points.

First of all, static content is never entirely static: contents will be probably updated in time and might even be real time. While recreating the bundle every time the content changes represents the quickest solution, it takes time – more than in real time at least. There have been big improvements in the speed of the tools when generating this bundle; it used to take way longer than today and support up to a few thousands pages, while today, with solutions such as partial builds, it can be mitigated. It is still not real time; real time content can only be handled through dynamic components on the client side.

Secondly, by relying on the delivery through services such as Netlify, S3, Vercel and so on, we’re leaving to the middleman to handle security and performance optimization for static files. We can also do it on our own, of course.

Third and last (but also probably the trickiest part), is that by having static files we move the concern for sessions and authentication/authorization to external microservices instead of the server. With careful reliance on Service Workers, and/or solutions such as Firebase, we can solve this. The JAM stack also strongly favours a serverless approach to server interactions: by writing simple functions in Node, to be deployed in the same hands-off approach from the same codebase (possibly even sharing code), we can handle just about everything as before with traditional AJAX requests.

Both the serverless approach and the delivery of static files is a big reduction in costs compared to deploying virtual servers, as we only use what we need and scale naturally as more the resources are required. But rarely accessed contents or functions do require some extra time as the provider has to “boot up” the context of the functions for us.

A common Use-Case: a Blog and its Pages

Static websites are really suited for delivering the contents of an editorial product. Text and images are usually not updated in real time, and the business requirements are more often aligned with the value proposition of static site generators:

- A safe environment with low attack surface for the public.

- Fast performance on all metrics, to boost the SEO and mobile performances.

- Low costs, in development, deployment and maintenance

This environment has been, for the past decades, very much dominated by WordPress and its themes, which provide a good enough solution for most companies and, since they are so commonly used, editors do not need to learn again how to do things. As WordPress developed its own API in the last decade, we can rely on it to provide the base for our contents and access the existing ecosystem and know-how, deploying it on a low cost solution such as WordPress.com or perhaps a small VPS. All that we really need is a safe way to get our content from our install to our static site generator, that will generate the page at build time calling the APIs. We could just as easily deploy an headless CMS or even a completely custom solution – on the frontend site it doesn’t really matter much.

Our choice for a static site generator can also be decided according to the skills of the developers working on the project. On the React side, both Gatsby and Next.js are very popular solutions, with Gatsby having an already established set of plugins and starters very similar to WordPress that can speed up the development. On the Vue side, Vuepress and Gridsome are two common solutions: the first one being the easiest of the two in terms of features and approach to content (by using Markdown files), while the second more similar to Gatsby, providing plugins and starters. Both Gridsome and Gatsby, in fact, use GraphQL as a lingua franca for our contents, so that we can integrate many sources and use them in a common way.

Last but not least, we can decide where to deploy our contents. There’s a huge number of possibilities, from CDNs to storages (such as S3) or many services that pride themselves on simplicity like Netlify and Heroku. Anyway, what we really need is a channel to deliver the bundle of the contents to our users; whenever we update our contents, we will simply call an API to trigger again the build process and reload the files.

An Example with Gatsby

To build an example solution, we’re going to use DigitalOcean to host our WordPress installation. Our generator will be Gatsby for this very specific example, but the concepts are quite similar for many of them. Note that we will be just using a function to build the pages, but many of these generators offer integration with external CMSs and might use GraphQL and such to do the queries; here is just a generic example.

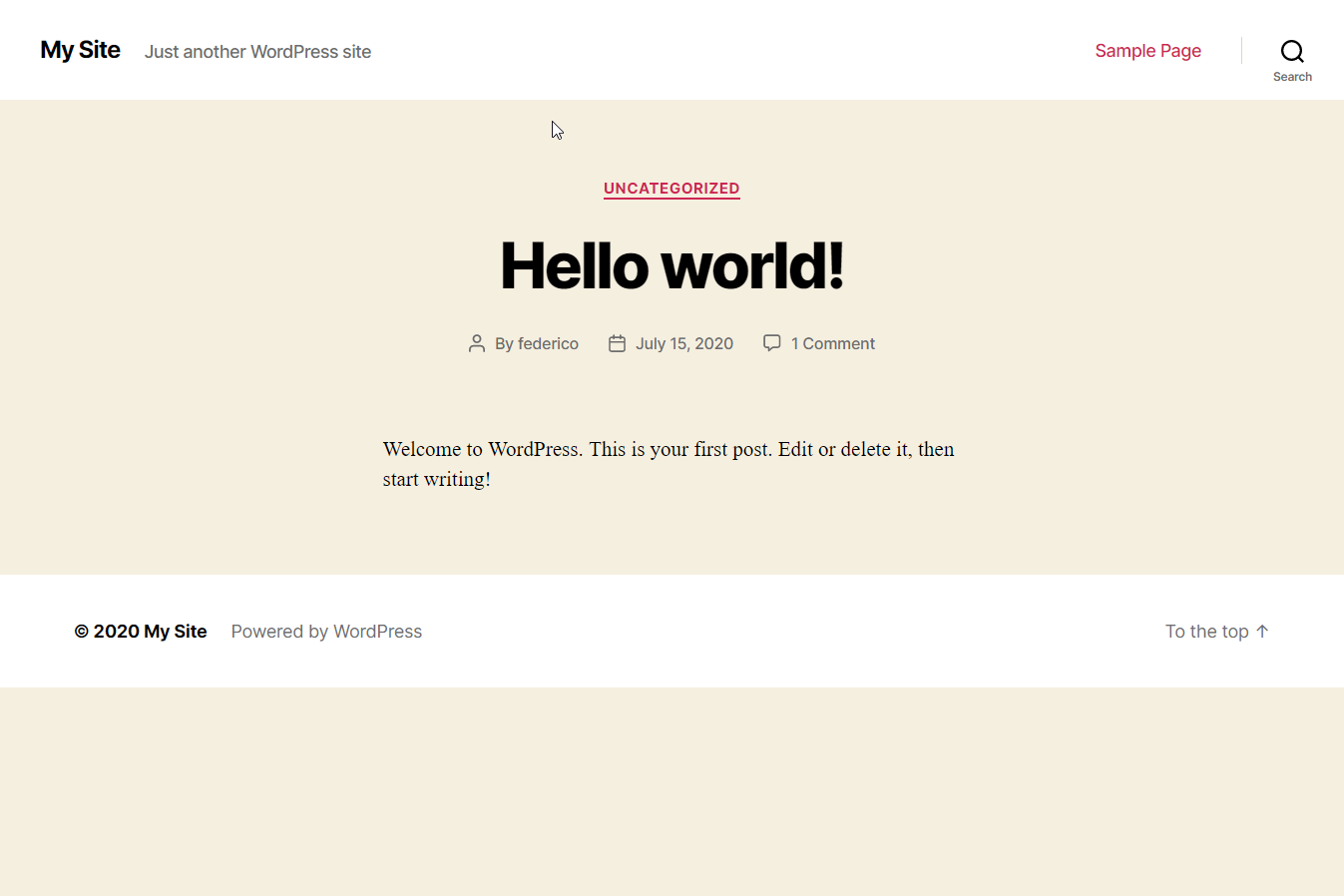

To begin, we created a droplet on DigitalOcean using their image for WordPress on Ubuntu 18.04. You can find more information about this on their website, as their wizard will do the bulk of the work for you. Don’t forget to follow the installation of WordPress itself. For this example, we’re not going to even configure a domain for our install, but you definitely want to use a proper configuration. Many hostings also offer simple solutions to host applications such as WordPress, and will do the job nicely.

Now that our WordPress is set up, we can start working on our frontend. First thing first, we create the project using the command line interface for Gatsby.

npm install -g gatsby-cli

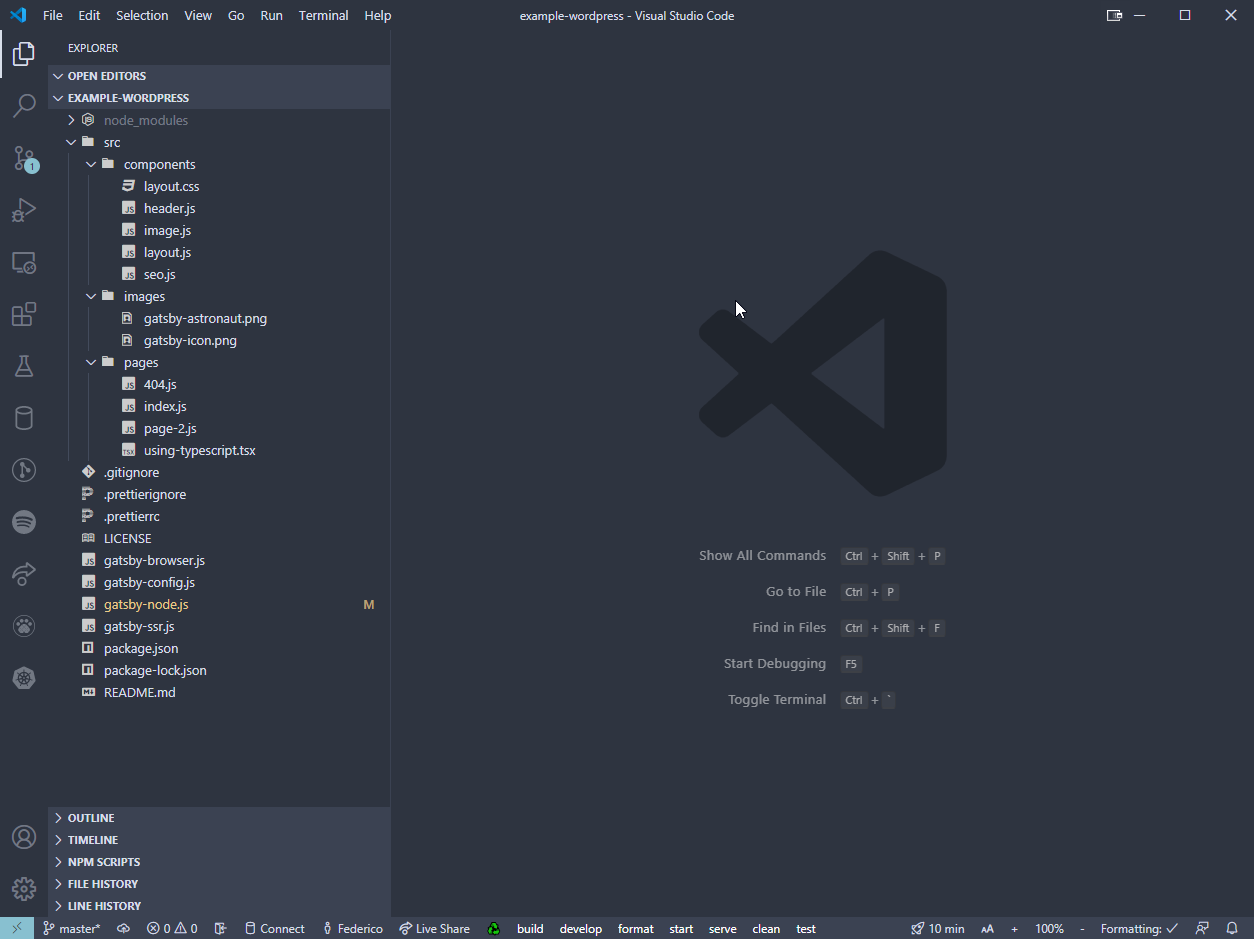

gatsby new example-wordpress

This creates our base project using the default starter kit from Gatsby. Inside the \example-wordpress\ we can find the modules needed already preinstalled, some configuration for styling the code (with Prettier), and the source code folder (\src\); the latter having inside both the folder for the React \components\ and the folder for the \pages\. Files inside the \pages\ folder will be accessible by default through their filename (for example, \page-2\ will be located at \example.com/page-2\).

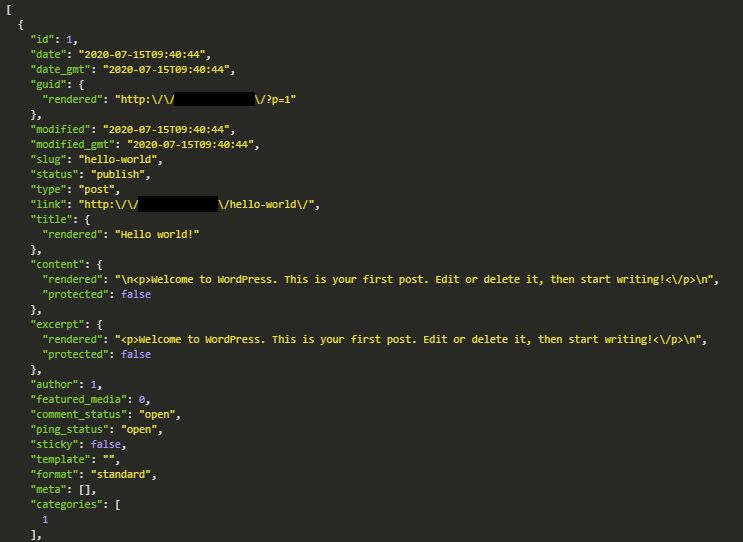

What we want to do is to hook up into the build process of Gatsby and generate our pages from the WordPress API. You can find more information about the APIs from the REST API Handbook, but the gist of it is that we’re requesting the posts resource from it using the correct endpoint. You can preview the available resources by going at the page \example.com\\wp-json\; we will be accessing the \wp\\v2\, under which we have the editorial contents, and query for the posts. Our URL will be something like \example.com/wp-json/wp/v2/posts\.

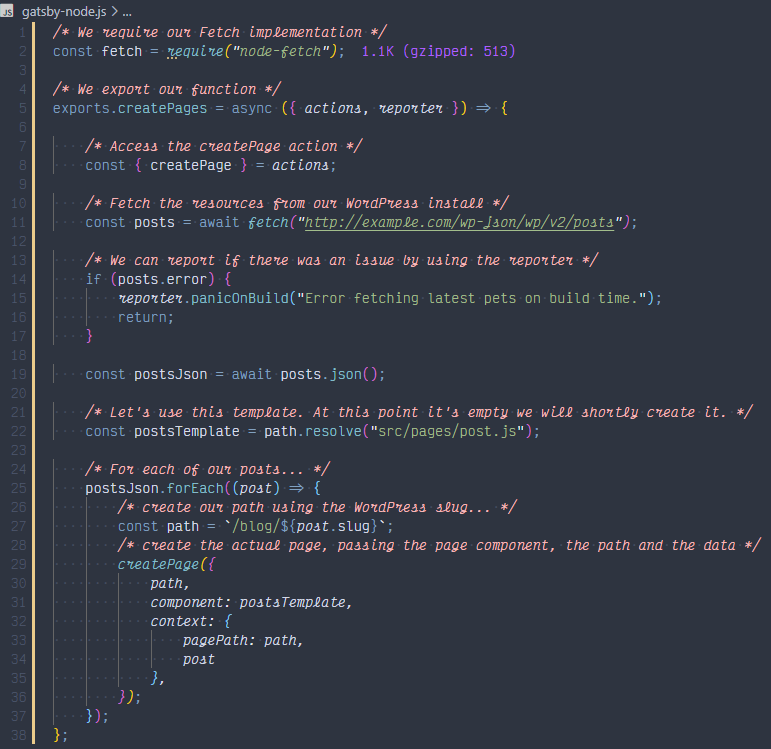

Now we just have to pull it inside Gatsby and build the pages. To do this, we open our project and navigate to the \gatsby-node.js\ file that should be in the root. We install and import the module \node-fetch\, so that we have an easy interface to get our resource by using:

npm install –save node-fetch

And putting at the top of the file our import:

_const fetch = require(\MARKDOWN_HASH03c697f1f26e7438c661b7bc6dd0f4b2MARKDOWNHASH);

Next, we hook up into the \createPages\ step of Gatsby. In order to do so, we will export an asynchronous method from our file called \createPages\, which receives an object with the \actions\ available to us and a \reporter\ object that can tell Gatsby if something went wrong. Inside this function, we fetch our posts and create a page for each of them.

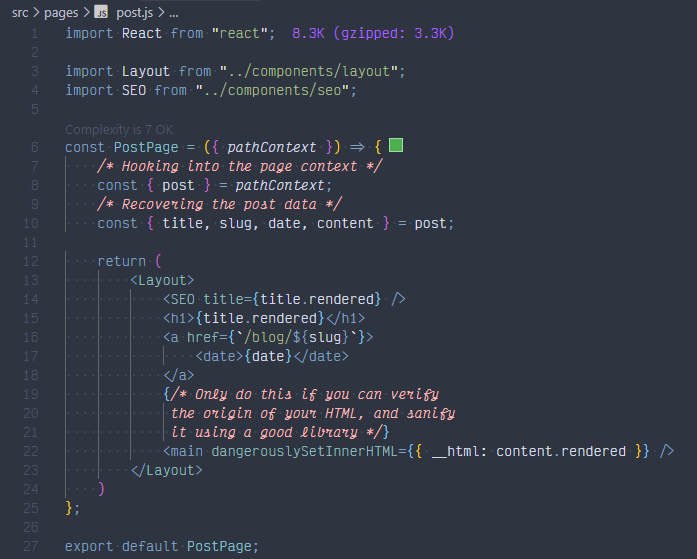

Let’s create the template page for the blog posts. We create a file in the \pages\ folder named \post.js\, and access the post data by reading it from the props of our page component.

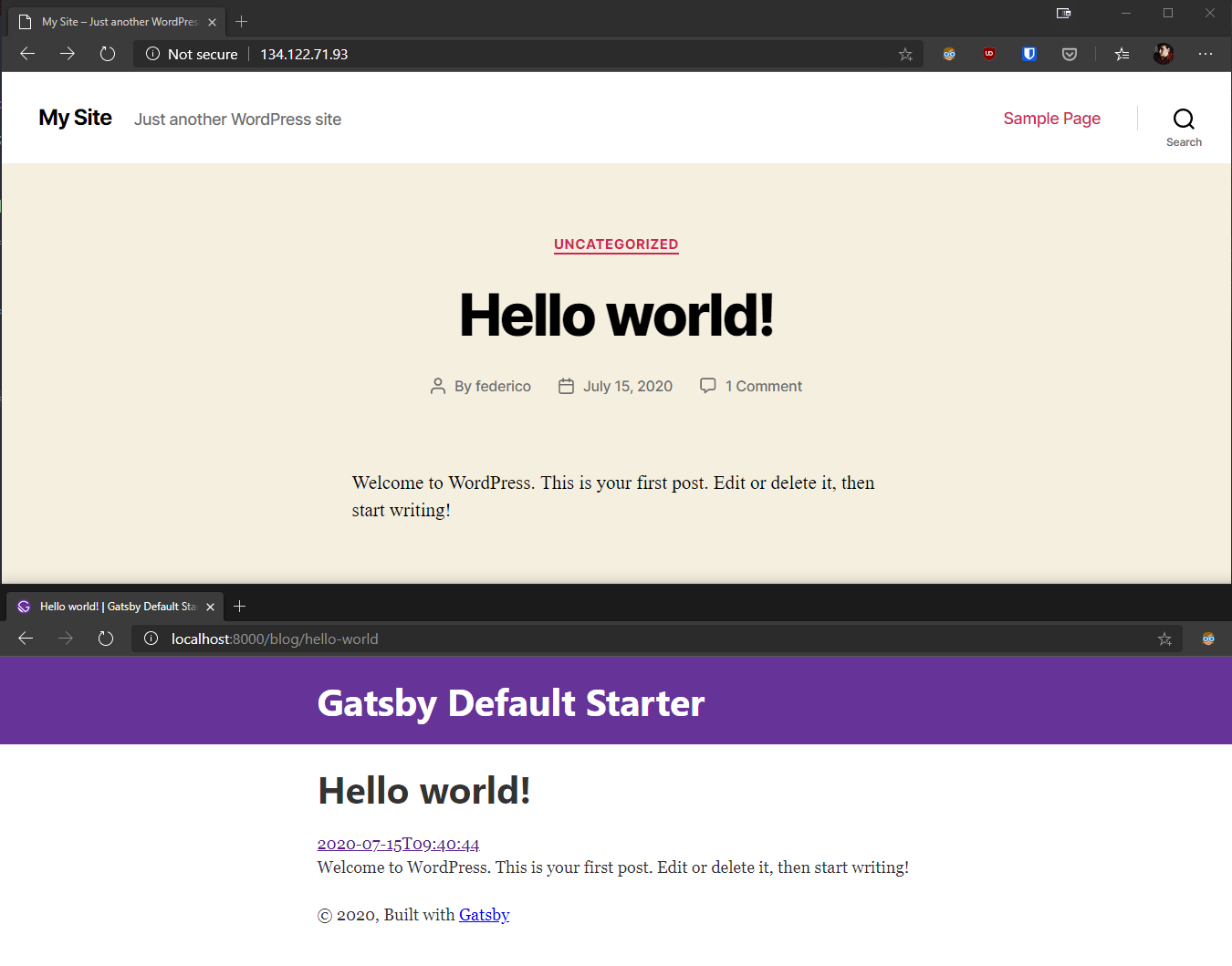

We should now have a corresponding page in our frontend:

This is of course just the beginning.

- To host our content online, we could rely on something like Netlify. We just push our project to Github, then add Netlify as an application.

- To trigger the rebuilding of our contents, we could for example make a call using cURL to our services on the \

save_post\hook. - We could build our taxonomy pages, either by using the API from WordPress or the posts JSON. To better integrate it into Gatsby (or Gridsome perhaps), we could add our posts as GraphQL nodes.

- A common criticism of this kind of solution is that editors don’t really have an idea of how the content will end up looking on the frontend. We can build a simple WYSIWYG editor on the frontend side by relying on a good library like Draft.js. Of course this also requires authentication and so forth. We could also share the same CSS and major HTML between both the WordPress environment and Gatsby.

- We could lock our WordPress APIs behind a simple authentication using either Apache or Nginx, as they’re quite common in this kind of setups. Logging in through Node is trivial.

Conclusions

Static site generators enable us to provide a good user experience and also good performance, with a bit more effort than using common CMSs such as WordPress as a monolithic approach. We can integrate different sources and create very custom solutions using modern scaffolding and tooling. However, it does require quite a bit more effort, and the disconnect between frontend and backend can be a pain point for our editors.

Author: Federico Muzzo, UX/UI Engineer @Bitrock